For the past 31 years[i], a conventionally-diversified portfolio consisting of 60% stocks and 40% bonds has provided investors with satisfying returns of +10.80% annually. This was the result of both stocks and bonds advancing strongly throughout that period. Better yet, stocks and bonds complimented each other nicely. When stocks returned +19.35% annually from the market low in 1982 to its peak in August 2000, bonds lagged somewhat (although still returning a substantial +10.34% annually). But in the period from the 2000 market peak to the 2009 market low, while stocks declined a sharp -43.51%, bonds balanced that with a strong +61.78% rally. More recently, both stocks and bonds have advanced, with the 60-40 portfolio gaining an annualized +15.36% from the market low in March 2009 to May 31, 2013.

The past 31 years was an unprecedented period for a 60-40 portfolio; one that wasn’t seen prior. In fact, as I wrote in my best-selling book, Jackass Investing: Don’t do it. Profit from it., “all of the real stock market returns over the past 111 years can be attributed to just an 18 year period – the great bull market that began in August 1982 and ended in August 2000. Without those years the real, inflation-adjusted return of stocks, without reinvesting dividends, was negative.”

Unfortunately for investors, the 60-40 results of the past 30 years aren’t likely to repeat in the near future. Here’s why not.

Return drivers for U.S. equities

There’s an ethos among equity investors that stocks provide an intrinsic return. This ethos is rooted in a depth of academic research that identifies an equity “risk premium” as the source of stock market returns. The equity risk premium is the “theory” that equities are destined to produce greater returns than less risky investments such as corporate bonds, simply because they ARE riskier.

In fact, the “research” supporting the equity risk premium is actually not research at all but merely an observation – an observation that over the past couple of centuries stock returns outperformed bonds. Then a postulate, the risk premium, was created to support that observation, which in turn was “proven” by the observed data. As you could likely surmise from the obvious circularity of the postulate and proof, this is wrong. The risk of investing in stocks has nothing at all to do with their returns. As I show in Jackass Investing, stock market returns are driven by three primary “return drivers”.

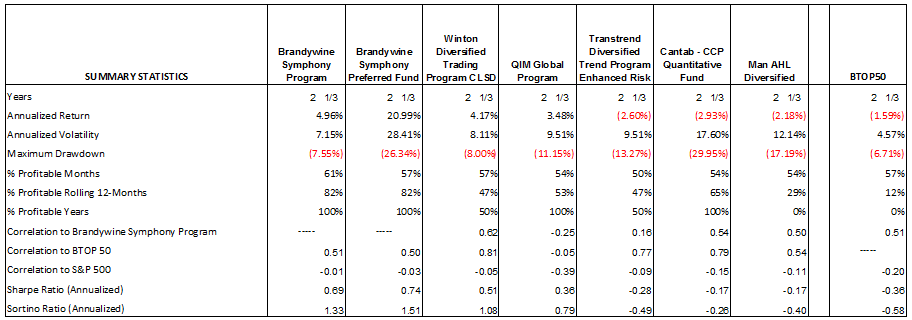

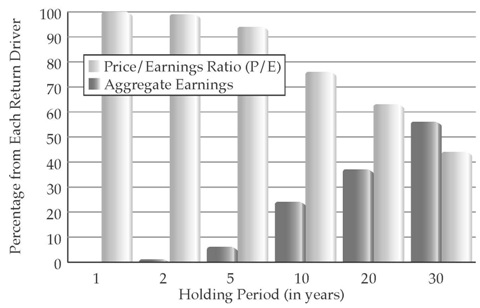

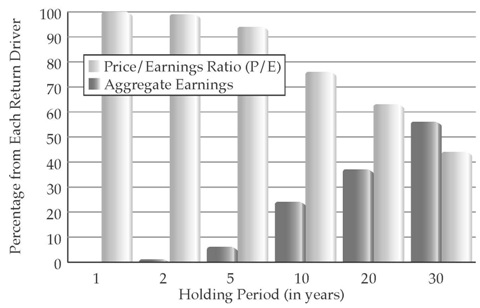

In the book’s first chapter I show how over the long term stock market returns are dominated by corporate earnings growth, and in the short-term (less than 20 years) by the multiplier (the “price/earnings” or “P/E” ratio) people are willing to pay for those earnings. The chart displaying this is reproduced here[ii]:

In the second chapter I display the fact that historically, dividends have provided 48% of the total return from U.S. equity investing over the period 1900 – 2010[iii]. (In most of the studies presented in my book and in this article, I use the S&P 500 total return index which includes dividends. The ETF that generally corresponds to the price and yield performance of the S&P 500 is SPY).

Knowing this, these were the three dominant return drivers that contributed to the stock market’s +11.88% annualized return over the past 31 years:

- 6.16% of the annual return was driven by the average annual profit growth of 6.16%

- 3.19% of the annual return was the result of the increase in the P/E ratio from 10 in 1982 to more than 23 at the end of 2012 (using the cyclically-adjusted P/E (“CAPE”) presented by Robert Shiller in his book Irrational Exuberance[iv])

- 2.53% of the annual return was due to the dividend rate starting the period at an historically high 6.24% in 1982 and averaging 2.53% throughout the period

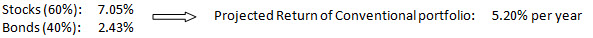

Going forward, if the P/E ratio reverts to its long-term average of 16.4, corporate profits grow at their historical average of +4.70%, and dividends increase at the same rate as corporate profits (and the dividend payout ratio increases to its long-term average), stocks will appreciate at just 7.05% per year over the next decade. Here’s the arithmetic.

Future returns from U.S. equities

To determine the likely return for the S&P 500 over the remainder of this decade we need three primary inputs:

- The rate of earnings growth for the companies underlying the index,

- The most likely P/E ratio people will pay for those earnings at year-end 2020, and

- The dividend yield for those stocks during the period.

Let’s look at each of these in turn.

Return contribution from earnings growth

Since 1900, the nominal (before inflation) average annual growth rate for companies in the S&P 500 has been 4.7%. Over the same period the average annual inflation rate has been 3.04%. For purposes of our projections I will assume these two variables continue at the same rates into the future. While I understand there are many people who expect a substantial increase in inflation, historically, that has also resulted in an increase in the nominal (before inflation) return for the S&P 500. So if that were to occur, while the nominal return from the S&P 500 would likely increase, the real (after inflation) rate of return would, on average, remain around the historical level of 1.7%. Because of this, I project the annual return contribution from earnings growth, between 2012 and the end of 2020, will be +4.70%.

Return contribution from investor sentiment

There are a variety of methods used to calculate the price/earnings ratio of a stock or stock index. The method I will use in this article is CAPE (“Cyclically Adjusted Price Earnings Ratio”), the ratio popularized by Robert Shiller in his book Irrational Exuberance. CAPE compares the S&P 500’s current price to the 10-year average of earnings. This has the benefit of smoothing earnings volatility to reduce the short-term impact of events such as the 2008 financial crisis. Over the past 113 years, CAPE has ranged from a low of 4.46 (in the depths of the Great Depression) to a high of 48.94 (at the peak of “dot-com” hysteria in 1999). The average CAPE over that period has been 18.63.

As of year-end 2012 CAPE stood at 23.37. Part of the reason the rate was above the long-term average was because the 10-year average earnings value used in the calculation was depressed by the effects of the Great Recession of 2008. In order to make the CAPE value in 2020 appear less elevated (compared to the long-term average) than it appears today due to the Great Recession, I will continue to walk forward the earnings average of the prior 10 years from 2013 through 2020, assuming average earnings growth based on the long-term average of 4.7%. This results in a growth rate of 6.8% for the 10-year earnings average from 2013 through 2020.

As a result of the combination of the increase in the 10-year average of profit growth and CAPE reverting to its long-term average, I project the annual return contribution from investor sentiment, between 2012 and the end of 2020, will be -0.72%.

Return contribution from dividends

The dividend yield on the S&P 500 at year-end 2012 was approximately 2.20%. This represents a dividend payout ratio of 36%. This figure is quite a bit lower than the 113 year average of 59%. If the payout ratio reverts to its long-term average, this will boost the dividend yield over the remainder of this decade. As a result of this, and assuming that dividends grow at the same rate as profits, which is 4.7% per year, I project the annual return contribution from dividends, between 2012 and the end of 2020, will be +3.07%.

Calculating the S&P 500 total return

We’re now left with a simple arithmetic problem to determine the projected average annual return for the S&P total return index, between 2012 and the end of 2020.

This is the sum of the contribution from each of the three return drivers:

Future returns from bonds

For the past 31 years the Barclay Aggregate Bond Index averaged annualized returns of 8.43%. Unfortunately, the two primary return drivers that contributed to that performance are both destined to provide much lower returns in the future. They are:

- The capital appreciation provided as the high interest rate of 13% that prevailed at the start of the period declined to just over 1% today, and

- The average yield of 5.74% on the 5-year Treasury note over the period.

With the Barclay Aggregate Bond Index now yielding just over 2%, and the U.S. Treasury 5-year note yielding 1.05%, the likely return from bonds over the remainder of this decade should be similar to the current yield on the Barclay Aggregate Bond Index, which, as represented by the iShares ETF (AGG) is 2.43%.

Calculating the return on the 60-40 portfolio

In summary then, based on the above straightforward analysis, from year-end 2012 through year-end 2020 we can expect the following return from a conventional 60-40 portfolio:

This is less than 1/2 the return earned over the past 31 years and approximately 1/3 the returns produced since the Great Recession low in March 2009. As I pointed out at the beginning of this article, 60-40 has always been a risky proposition; returns are earned in a “lumpy” fashion. Without the tailwinds of low P/E, high dividend yield and high interest rates, in the future those lumpy returns will be earned in relation to a lower trendline of overall performance. Also, while these projections are based on a sound analysis of the return drivers powering the 60-40 portfolio’s performance, they are certainly not absolute. Already, in the first 5 months of the 8-year projection period (January 2013 through December 2020), the 60-40 portfolio has gained more than 5%, twice that expected from these projections.

Portfolio diversification is the one true “free lunch” of investing, where you can achieve both greater returns and less risk. But, as can be seen by its reliance on just four return drivers, the conventional 60-40 portfolio does not provide true portfolio diversification. When those four return drivers underperform, as is indicated by the projections in this article, performance will suffer. True portfolio diversification can only be obtained by increasing diversification across dozens of return drivers. I give examples of a truly diversified portfolio in the final chapter of my book, and am pleased to provide a complimentary link to that chapter here: Myth 20. While some people may prefer to gamble on a less-diversified 60-40 portfolio, as my book shows, in the longer-term, true portfolio diversification can lead to both increased returns and reduced risk.

————————————————–

[i] From the market low at the end of July 1982 through May 31, 2013.

[ii] Michael Dever, Jackass Investing: Don’t do it. Profit from it. (Thornton: Ignite Publications, 2011).

This study uses linear regression analysis to determine the degree to which variance in the S&P 500 Total Return Index over various holding periods (1, 2, 5, 10, 20 and 30 years) was explained by the changes in nominal earnings and changes in P/E. A 10 year average was used to represent both the nominal earnings and the “E” in the P/E in order to reduce the impact of economic cycles. The regression analysis included three separate regression calculations for each holding period. The first regression measured the goodness of fit for changes in average earnings versus S&P total returns. The second regression measured the goodness of fit for changes in the P/E versus S&P total return. The third regression includes the two parameters, average earnings and P/E, versus S&P 500 total returns. Since linear regression assumes orthogonality of the independent variables, that assumption was tested on all of the holding period data. The Percentage change in the nominal earnings versus the P/E ratio had R2 values ranging from 2% to 6% across all holding periods, suggesting the two regression parameters are mostly independent of each other. Furthermore, the two parameter regressions were found to explain greater than 93% of the variance in the S&P 500 total return over each holding period. Since nearly all of the variance in the S&P 500 return is captured by the two parameter regression I normalized the R2 result from each of the single parameter regressions to 100% for use in Figure 3. The use of the single parameter R2 to measure the explanatory power of the S&P 500 total return for the two regression variables is an approximation. The subtle (

[iii] Annualized return of S&P 500 TR index 1900 – 2010: +9.51%. Annualized return of S&P 500 w/o reinvesting dividends: +4.92%. Contribution of dividends = (9.51 – 4.92) / 9.51 = 48%.

[iv] The cyclically-adjusted P/E (“CAPE”) used by Robert Shiller in his book: Robert J. Shiller, Irrational Exuberance (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000, 2005, updated). Data used in Shiller book and for S&P 500 Total Return performance available at: http://www.econ.yale.edu/~shiller/data/ie_data.xls. Retrieved February 14, 2011.

[v] This was the rate on the 5 year U.S. government bond. Five years is used as that is the approximate average duration of the Barclay Aggregate Bond Index.