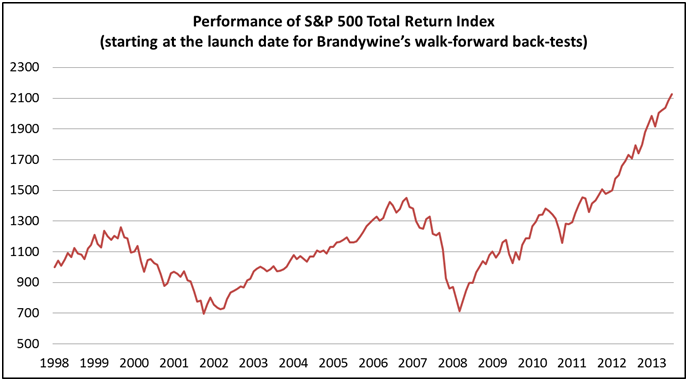

This is an update to the article I wrote in mid-2013 that projected the future returns to be earned from stocks and bonds through the remainder of this decade. The article was based on research I conducted in writing my best-selling book, Jackass Investing: Don’t do it. Profit from it [i] .

Unfortunately, for people intent on adhering to a conventional 60-40 portfolio, or gambling [ii] their returns on placing money primarily in stocks, future returns do not look promising. The projected returns are lower than most people anticipate for two primary reasons:

- The stock market rally that has taken place over the past few years has dramatically increased the multiple that people are now paying for stocks and unless “this time is different” has the effect of reducing today’s future return potential, and

- Current profit margins have expanded to a level that is well above their long-term average. Unless “this time is different” a return to a more normal level will serve as a drag on profits over the remainder of this decade.

But before we get into the basis for my projection, let’s take a look at the three primary return drivers that power stock market returns. I outline these in the first two chapters [iii] of my book:

- Corporate earnings growth

- Investor sentiment

- Dividends

Now I’ll show how each of these returns drivers is projected to contribute to the future returns from stocks.

Return contribution from corporate earnings growth

Since 1900, earnings growth for companies in the S&P 500 (and its predecessor indexes) has averaged 4.73% [iv] . Because we use a 10-year average of earnings (as described in the next section) to calculate the likely level of stocks at the end of the decade, the effect of dropping off the poor earnings during the financial crisis has the effect of increasing the real 10-year average earnings growth rate over the remainder of this decade to above this level. For example, if profit margins remain at today’s level, earnings will grow at 7.19% from year-end 2013 to year-end 2020.

Unfortunately for future returns however, today’s profit margins are a fair amount above the longer-term average. Depending on the time period measured and companies included in the measurement, a ‘normal’ profit margin is approximately 7% [v] , while today’s profit margin on the S&P 500 is in the range of 9.5% [vi] . There are a number of factors that have contributed to today’s higher profit margins, among them low interest rates, constrained payroll costs and capital expenditures, and increased profits (and lower taxes) derived from non-US business. And there are those who contend that these changes are structural and will persist. Perhaps. But to accept this is to believe that “this time is different.”

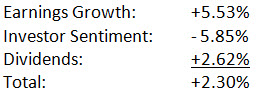

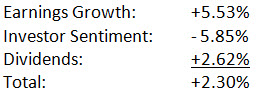

As a result, I believe that profit margins are likely to decline to the longer-term average of 7% by year-end 2020. As profit margins revert towards their long-term average, earnings growth will be subdued. To expect something different is betting against the odds. The result is that corporate profits on the S&P 500 are likely to grow at a 5.53% annual rate.

Return contribution from investor sentiment

In my book I show that investor sentiment is the dominant return driver for stocks during periods of less than 20 years. Perhaps surprisingly, today, less than five years after the dramatic losses suffered by the world’s stock markets during the financial crisis, investor sentiment is approaching historical highs. This is evident in a variety of indicators, such as investor surveys [vii] and stock fund inflows [viii] . But the measure we use, which confirms the optimism exhibited by these other measures, is the cyclically-adjusted price-earnings ratio (“CAPE”).

CAPE was popularized by Robert Shiller in his book Irrational Exuberance and compares the S&P 500’s current price to the 10-year average of earnings. This has the benefit of smoothing earnings to reduce the impact of interim events, such as the financial crisis. Over the past 114 years CAPE has averaged 16.45. As of year-end 2013, due to the strong stock market rally of the past few years, CAPE has inflated to 25.09.

Unless “this time is different,” to believe that CAPE will remain at a new “permanently high plateau [ix] ” is to bet against the odds. Over the remainder of this decade CAPE is more likely to revert to its long-term average. The result will be an annual drag on stock market appreciation of -5.85% [x] .

Return contribution from dividends

The dividend yield on the S&P 500 at year-end 2013 was approximately 1.91%. This represents a dividend payout ratio of 37%. This payout ratio is quite a bit lower than the 114 year average of 59%. If the payout ratio reverts to its long-term average, this will boost the dividend yield over the remainder of this decade. As a result of this, and assuming that dividends compound this effect while also increasing along with corporate profits, I project the annual return contribution from dividends, between 2013 and the end of 2020, will be +2.62%.

Calculating the S&P 500 total return

We’re now left with a calculation to determine the projected average annual return for the S&P total return index, between year-end 2013 and year-end 2020.

This is the sum of the contribution from each of the three return drivers:

This performance is dramatically lower than what conventional investment wisdom has led people to expect. Even if profit margins remain at today’s high levels, the total return from stocks will be, at 4.3%, only half of what people have come to expect. The math is rather straightforward. To expect a different result than what is shown here is to insist that “this time is different.”

Return contribution from bonds

For the past 32 years the Barclay Aggregate Bond Index averaged annualized returns of 8.46%. Unfortunately, the two primary return drivers that contributed to that performance, although more favorable since I wrote my original article, are both destined to provide much lower returns in the future. They are:

- The capital appreciation provided as the high interest rate of 13% that prevailed at the start of the period declined to 1.75% today, [xi] and

- The average yield of 5.79% (on the 5-year Treasury note, which approximates the yield on the Index) over the period.

With the Barclay Aggregate Bond Index now yielding just over 2%, the likely return from bonds over the remainder of this decade (based on the fact that historically, the yield on the Barclay Aggregate Bond Index is predictive of total returns over the following 5-10 years) should be similar to the current yield on the Barclay Aggregate Bond Index, which, as represented by the iShares ETF (AGG) is 2.32%. To believe otherwise would be to believe that “this time is different.”

Calculating the return on the 60-40 portfolio

In summary then, based on the above straightforward analysis, from year-end 2013 through year-end 2020 we can expect the following return from a conventional 60-40 portfolio:

This is obviously much lower than what people have come to expect from a conventionally-diversified portfolio. It is also likely insufficient to meet most people’s financial needs. This doesn’t mean stocks couldn’t go up 30% again in 2014. They could. But they could also drop 30%. In fact, the lower projected return does not mean lower volatility. History shows that during periods with similar CAPE levels as today, volatility has actually been higher than normal [xii] . So while we’re looking at low returns over the next seven years, we’re also looking at above average volatility of those low returns. Clearly, this is a sub-optimal environment in which to entrust your money to a 60-40 “poor-folio.”

But this is not a unique situation. Conventional investment wisdom has always encouraged gambling, rather than investing. Due to its reliance on just four return drivers, the conventional 60-40 portfolio has never provided true portfolio diversification and has always exposed people to unnecessary risks relative to the potential return (my definition of “Jackass Investing”). When those four return drivers underperform, as is indicated by the projections in this article, performance will suffer, but the risks remain. The dramatic losses in 2001 and 2008 should serve as a warning. They are not exceptions.

But there is a better way.

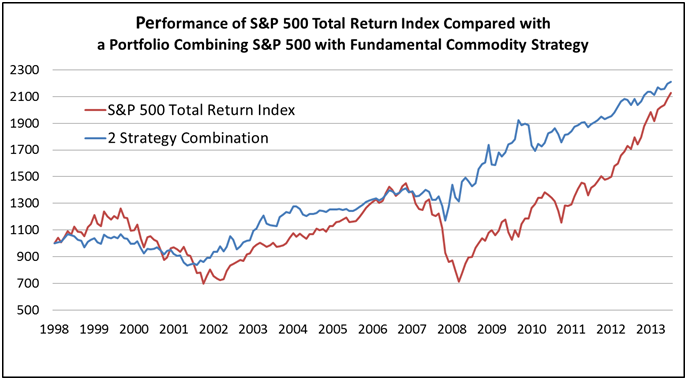

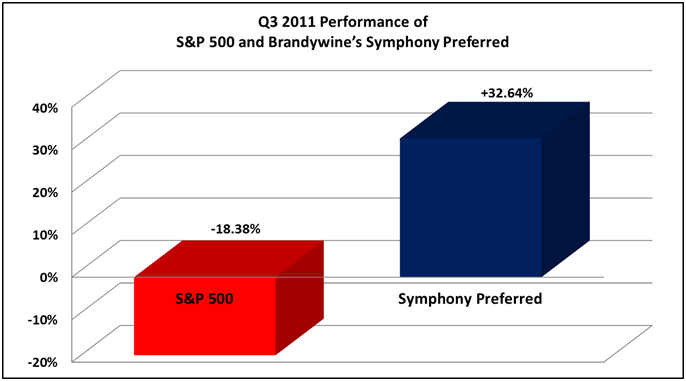

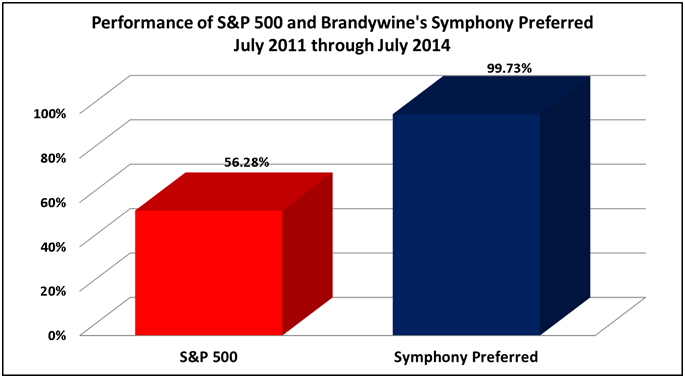

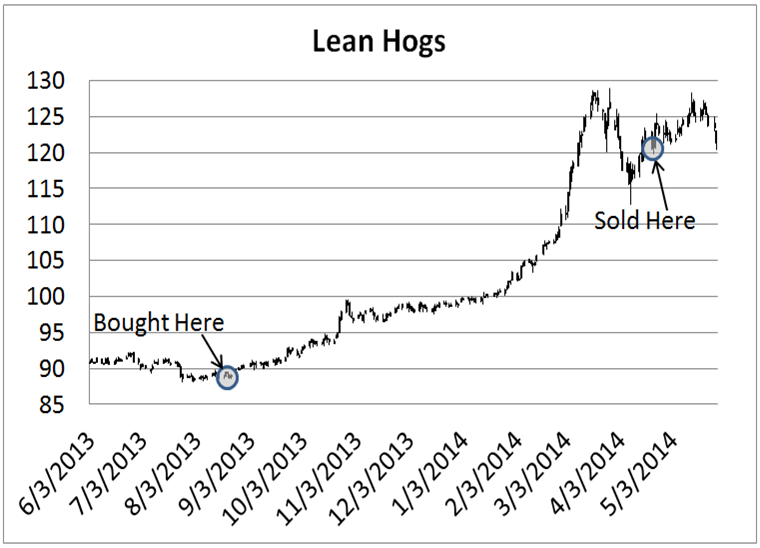

Increasing returns and reducing risk with Return Driver based investing

Portfolio diversification is the one true “free lunch” of investing, where you can achieve both greater returns and less risk. But “true” portfolio diversification can only be obtained by diversifying your portfolio across multiple return drivers [xiii] . I give examples of a truly diversified portfolio in the final chapter [xiv] of my book, and I am pleased to provide a complimentary link to that chapter here: Myth 20. While some people may prefer to gamble on a less-diversified 60-40 portfolio, as my book shows, in the longer-term, true portfolio diversification can lead to both increased returns and reduced risk. And especially today, the odds do not favor a 60-40 gambling approach.

____________________________________________________________________

[i] Learn more about the book at www.JackassInvesting.com .

[ii] I refer to holding heavy positions in stocks as “gambling” Because people that do so are taking unnecessary risks with their money (meaning they could earn the same returns with less risk if they properly diversified their portfolios). You can read the chapter on gambling vs. investing here: http://bit.ly/utWsNy

[iii] I have made available complimentary eBook versions of the Introduction and first two chapters of my best-seller at the following links: http://tinyurl.com/qxt8e2h and http://bit.ly/xW2xuS

[iv] Robert J. Shiller, Irrational Exuberance (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000, 2005 updated). Data provided from a spreadsheet available at http://www.irrationalexuberance.com/

[v] David Bianco, “Deutsche Bank Securities Inc. US Equity insights,” December 12, 2013, pg. 72.

[vi] S&P reports profit margins on the S&P 500 as of June 2013 at 9.5%. Available under “Additional info, then “Index Earnings” at http://us.spindices.com/indices/equity/sp-500

[vii] The Investors Intelligence survey of December 17, 2013 shows more than four times as many bulls as bears. This is one of the highest readings in the history of the indicator and is greater than the ratio at both the 2000 and 2007 market peaks. Historically, measures greater than three are indicative of market tops.

[viii] I present an actual trading strategy based on stock fund money flows in the “Action Section” for Jackass investing). You can read about the trading strategy starting on page 19 of the Action Section at: https://jackassinvesting.com/action/index.php.

[ix] This was the famous quote pronounced by the noted economist Irving Fisher immediately prior to the stock market crash of 1929, when he stated that the stock market had reached “a permanently high plateau.” His reputation never recovered from that gaffe.

[x] If CAPE today was equal to its long-term average the S&P500 would be at 1192, a 34.45% decline from the year-end 2013 price of 1818. This equates to an annualized decline of 5.85%.

[xi] This was the rate on the 5 year U.S. government bond. Five years is used as that is the approximate average duration of the Barclay Aggregate Bond Index.

[xii] Shiller calculates that the forward three year volatility of S&P 500 is 15.55% when CAPE>=25 and 12.77% when CAPE<25.

[xiii] I discuss returns drivers in the Introduction to my book, which you can read here: http://tinyurl.com/q3eu7qm

[xiv] I have made available a complimentary eBook version of the final chapter of my best-seller at the following link: http://bit.ly/vxDo6v